This is an extended form of the short presentation I made at the 3rd International Open Data Conference today.

I’m working with Omidyar Network to document – through a selection of case studies mainly based in the UK – the impact so far of government open data policies. There are a lot of people thinking about open data impact right now, not least my companions on this panel, and I wanted to take this opportunity to briefly lay out my perspective on the issue, which as I mentioned already is grounded for the most part in the developed world.

When the UK and US governments adopted the open data policies that have led to them being leaders in this field, they did so on a prospectus of potential, and not proof. Open data policies promise to deliver economic efficiencies, governance gains, and social and environmental goods for what in government spending terms is a relatively low initial investment. They promise to keep bureaucracies one step ahead of the internet’s disintermediating power. Sold as such, it’s easy to see why governments in the midst of a global financial crisis and technological revolution bought into open data.

Great expectations

Our expectations have been set high, perhaps too high, in terms of what open data will deliver. Indeed, searching for tangible impacts at scale only three or four years after implementing a long-term policy change such as opening government data, we may yet be disappointed. And it would be a great shame if that disappointment led to disengagement with open data policy. Thankfully there are some front-runners, some stories we can tell about where open data is making a difference right now, and I hope these stories are enough to keep us on the right track, towards a world of open by default.

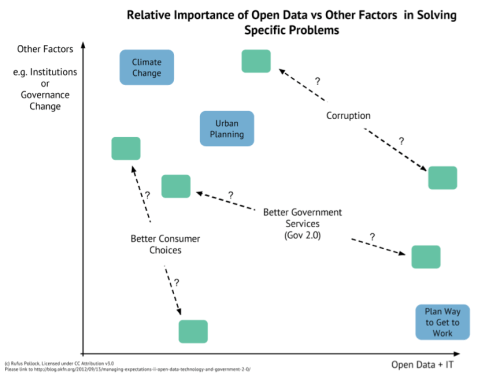

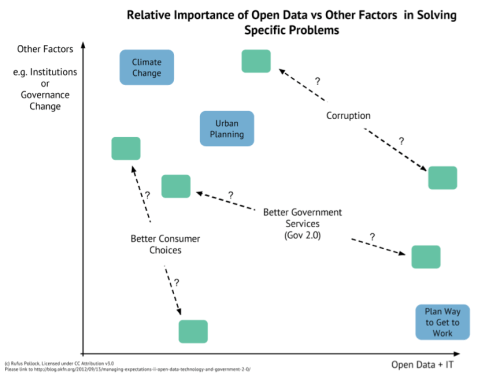

But we also need to be realistic about how much other factors, factors beyond the availability of information through open government data, affect the impacts we want to see. I want to show you this graph devised by Rufus Pollock of Open Knowledge:

Seeing this graph was a lightbulb moment for me. At a basic level, it illustrates the vast range of issues upon which we expect open data to have some effect. But it’s also a reminder that, as Rufus puts it, open data is a complement, not a substitute, for institutional change. We can’t expect unicorns and rainbows just by creating another CKAN instance. Most of what open data will achieve, it will achieve in partnership with some other kind of hard work.

Elusive evidence

Back to those good news stories. A study by Deloitte for the UK’s Department of Business estimated that by opening up their transport data, London’s transit authority netted efficiency savings of £58 million for London’s transport users in 2012. As the authors of that study observed, that is a considerable percentage of the projected annual savings that were used to justify the creation of an entirely new and very expensive high speed rail link in another part of the UK.

Playing around with numbers is one of the nicest ways to talk about impact, and in countries like the UK, where the civil service has actually created standard estimates for what an hour of my time is worth to me, it’s relatively easy to do. But talking about the wider social or political impacts that flow from the release of a particular data set is a lot trickier.

Even if you start trying to equate a country’s open data policy with shifts in its ranking on this or that social or political global performance indicator (and those sorts of indices bring their own issues with them), you’ll find causality hard to prove, not least because such indices are extremely high level, and the open data value chain is very long indeed. And you can add to this the problem that most studies designed to measure impact want their protagonists to have a set of goals they’re working towards, and that open data, by contrast, says “we’re releasing this to the world precisely because we believe we alone don’t know all the great things to do with it”.

Story-telling

Hard problems like this are of course great for academics. But I’m not an academic. My background is in journalism and activism. Essentially, I write stories. And right now, when it comes to open data impact, I don’t think that completely disqualifies me from the job at hand.

The best example we have so far of benchmarking open data impact is the Worldwide Web Foundation’s Open Data Barometer. And the way they measure impact is – they see how often open data is mentioned in the press and online. This is, in my mind, pretty much equivalent to measuring how good a story it is.

My stories don’t need fairytale castles or knights in shining armour, but they do need to resonate with someone who is unlikely to ever attend a hack day, or know what a Hadoop cluster is. So if you think you are sitting on such a story, or you know someone else who might be, I’d urge you to come and find me over the next couple of days.

Thank you very much.